You overdraw from your savings account. The bank doesn’t notice. You do it again. Same. And again. Same. What do you do? (A) Stop doing it. (B) Tell the bank about the glitch. (C) Live the life you’ve always dreamed of.

This is the true story of the man who chose C—thanks to more than 1.5 million bucks in “free” cash.

The greatest adventures happen when you least expect them. And on July 15, 2010, Luke “Milky” Moore never thought one of the greatest in recent memory was about to start for him.

Then again, not much ever went down in Goulburn, Australia, his sleepy hometown two hours into the barren brown hills southwest of Sydney. Goulburn’s biggest claim is its roadside attraction, the Big Merino, aka Rambo: a fifty-foot-tall concrete ram with a proportionally huge and hideous scrotum. For the twenty-three thousand locals, the main pastime is “slapping the pokies”—playing the electronic poker machines that fill every pub, kebab shop, and lawn-bowling club—with the hope of winning big enough to leave Rambo in the dust. But Milky, an affable blond twenty-three-year-old nicknamed for his likeness to the child star of the Milkybar candy commercials (think the Australian version of Mikey from the Life cereal ads), never counted on luck to make him rich.

Though he grew up comfortably—his father, Brett, was a bank executive, and his mother, Annette, a child-care supervisor—he’d been employed since thirteen, bagging groceries, mowing lawns, selling insurance. He was a bright student, but he opted to forgo college for work. “I always thought I’d be a millionaire one day,” he says in his thick Australian accent. While his mates were out drunkenly hunting wild boar, Milky was investing in hedge funds, and at nineteen he bought his own home, for himself and his high school sweetheart, Megan.

But then, in the fall of 2008, the life he’d worked so hard to achieve took a series of tragic turns. It started with the stock-market crash, which depleted his $50,000 life savings. With Goulburn’s economy in turmoil, he lost his job as a forklift driver. A few months later, he was driving in the early-morning darkness to paint happy birthday on a boulder near town to surprise Megan when he fell asleep at the wheel of his white Mitsubishi pickup—and drifted right into the path of an 18-wheeler, which plowed over his truck.

He awoke hanging out his shattered window covered in purple and black paint—but, miraculously, alive. “It was incredible that he survived,” recalls his father. Milky had a broken collarbone, arm, and ribs, and a ruptured spleen—but the scars ran deeper. He fell into a crippling depression, barely able to drag himself from bed or hold on to the job his father had helped him get as a teller at his bank. Adding to the pressure, his mother was suffering from a debilitating degenerative back disease, sometimes unable to get out of bed herself—leaving Milky to care for his year-old brother, Noah. It wasn’t long before his relationship with Megan ended under the strain, and Milky assumed the blame. By mid-2010, he was broke, alone, unemployed, and on the brink of foreclosure.

And that’s just when life suddenly gave him the equivalent of a royal flush on the pokies. It happened on July 15, the day his biweekly mortgage payment was due. With no money in the bank, Milky was bracing himself for the beginning of the end. But then something strange happened. The automatic debit—500 Australian dollars—went from his savings account at his bank, St. George, into his mortgage account. Two weeks later, it happened again. When he checked his balance, he could see that he had racked up the corresponding debt, and interest, under his name. Once he hit the limit, he assumed, the overdrafts would surely stop.

But they didn’t. Fortnight after fortnight, his mortgage got paid. Thinking this crazy, he put in a request for $5,000 to be transferred to his mortgage account. A couple days later, he called his bank to check on the transfer—figuring, at worst, he had reached his limit. “Did that go through?” he asked the teller, who told him casually, “Yes, that’s all paid.” A few days after that, on a lark, he called St. George and asked the bank to transfer $50,000 to his mortgage account. “I was literally thinking that I’ll just wing it and see if it works,” he recalls. And sure enough, it did. The $50,000 deficit was charged on his savings account, but the bank didn’t seem to notice, or, if it did, it didn’t care. It was like getting a free, unlimited loan. “I probably had a bit of a smile on my face then,” he says. “Not smiling because I was thinking I was scamming the bank, but smiling because I was like, ‘This is my fresh start.’”

By the time he sold his home a year later, he’d paid down his mortgage so much from the overdrafts that he cleared $150,000 (US$115,000).

Though he’d been quiet about this so far, he finally confided in a friend. “What do you reckon I do?” Milky asked him. What do you do, in other words, when you’re single, twenty-four, and just got a pile of free money from the bank? No-brainer, his friend replied. “Let’s party!”

Milky was going to Paradise.

Surfers Paradise is the crown jewel of the Gold Coast, the pristine swath of beaches along Australia’s eastern shore. It has the nightlife of Vegas and the ocean views of San Diego, with high-rise resorts lining the two-mile crescent shore. It’s exactly where you want to move if you’re a young guy with money to burn. Oh, and a cranky old red Alfa Romeo—which Milky had bought shortly before moving there in July 2011. As far as his family was concerned, it was just the move for him to get over his accident, his depression, and his breakup with Megan, and start again. “You need to get out of Goulburn,” his father compassionately said.

With $150,000, Milky had a big enough nest egg to live on for a long while. Booking himself into a beachside hotel, he soaked in the scene. For a country boy—or “bogan,” Aussie slang for “redneck”—who rarely left Rambo’s shadow, it really was paradise. By day, he took to the beach, bodysurfing the warm blue waves and chatting up the tourists and locals. By night, he cruised the bars along the palm-lined drag of Orchid Avenue: slapping the pokies, hitting up the strip clubs, and dancing to Kylie Minogue with the endless parade of sun-kissed girls. It was, as he often drawled, “beauuuutiful.”

In fact, it was so damn beauuuutiful he just couldn’t help but spend his cash. At first, it was innocent enough: picking up an extra round of beers here, treating a mate to a lap dance there. The days and nights quickly slipped into weeks of drinking, dancing, and casual sex. He moved into an apartment with a shady ex-coworker whom he had worked with briefly back home. When he asked to borrow $20,000 for hookers and blow, Milky was happy to oblige. For Milky, who’d never indulged in either, it was too much for this bogan to turn away—and he, as he puts it with a sheepish laugh, “became a bit feral.”

All parties end eventually, though, and one morning in December 2011, six months after he moved to Surfers, Milky’s bash crashed. His ex-coworker was gone, along with the money he’d lent him. When Milky called, the phone went to voicemail, and then nothing at all. And as for the rest of the $150,000 that was supposed to last him for ages, he’d pissed it away. Even worse, this happened on Christmas, his first away from his family. The old depression started sinking in as he looked back on what he’d lost: his house, his job, Megan. “I’ve had a few good opportunities in my life to make something of myself,” he says, “and I’ve fucked up every single one.”

But then he realized he had another lifeline: his St. George account. Though he hadn’t used it since he had left for Surfers, it was still there. There was just one problem: The overdrafts only worked for direct debits, meaning he couldn’t just go to an ATM and take out cash. He had to somehow get St. George to transfer money into another account from which he could withdraw.

And that’s when it hit him: PayPal. He’d already been using a PayPal account for his online purchases and was transferring money between it and an account he’d opened at another bank, National Australia Bank. So he winged it again, figuring that, as always, the worst St. George could say was no. He called the bank and requested a small transfer to see if it would work. As he sat anxiously at his laptop inside his hotel room, he kept hitting refresh on his browser as he checked his PayPal account.

Then his eyes widened. It worked—the money had gone through. He then requested it be sent from PayPal to NAB, from which he could withdraw cash. With the money in NAB, he headed out past the tourists on Orchid Avenue, slipped his card into an ATM near a pub, and tried taking out a few hundred dollars as a test. The seconds after his request ticked interminably, as his life hung in the balance. And then, like the ultimate pokey machine, the ATM began spitting out a stack of colorful polymer banknotes into his hand. Holy shit, he realized, I can get as much money as I want.

Milky needed help with the Maserati. Using his unlimited new bankroll, he bought it on GraysOnline, one of Australia’s biggest auction sites, for around $36,000. The car was silver and had “like, mad cream leather,” as he puts it, and needed to be picked up in Sydney. His Alfa Romeo had been on the fritz lately, so instead of taking a bus for two hours, he thought, Fuck it, I’ll just buy another car to get there: a candy-orange Hyundai Veloster.

Milky and a friend drove the Veloster to Sydney to pick up the Maserati, but not before stopping at the strip clubs in King’s Cross, the most notorious red-light district in Australia. Milky was known for being the generous sort. “He’s the kind of guy who’s always looking out for you,” says one of his older sisters, Sarah. And yet after buying round upon round of lap dances and drinks, he still was a bit taken aback when a beautiful dark-haired stripper, Jessica, slunk up to him and asked if “you might be interested in, like, taking me home or whatever.”

For a price, that was—including her friend. But Milky, encouraged by his buddy, was again happy to oblige. He booked the swankiest casino suite he could find for the group. When he and his friend woke up, there was only one thing to do: go to Thailand. Milky bought plane tickets to Phuket and a suite at a lavish beachside resort. They spent the next couple weeks partying in the streets and bodysurfing all day. The booze, the women, the weed—they flowed as quickly and endlessly as the cash he could take from the closest ATM. And when people asked how he had become so rich, he had just the answer. “I’m the Milkybar kid,” he’d say. “I still get mad royalties!”

Yet every time he went to take out more money, his heart raced as he feared that at any moment the bank would cut off his overdrafts. He kept reassuring himself that he wasn’t stealing the money, he was borrowing it—and if he did get cut off, he would find a way to pay it back. “I’d blow a whole heap of money all the time,” he recalls. “But then I’d try to save.” While some might have put money in real estate or the stock market, or simply buried cash in the outback, Milky returned to Surfers with his own twenty-something’s version of an investment plan: collecting celebrity memorabilia.

Back in Surfers, he’d spend the afternoon surfing GraysOnline on his laptop in the penthouse apartment he’d rented over the pubs on Orchid Avenue. He bought whatever caught his fancy: a signed Michael Jordan jersey, a signed Amy Winehouse drumhead, a framed Princess Di tenner by Banksy. He ordered up autographed pictures of his favorite artists: the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Kiss, the Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson, and Bob Dylan. He bought art, a certified Salvador Dalí, and a few by Pro Hart, considered the father of Australian outback painting.

Milky needed someplace to store all the stuff, and the safest place he could think of was back in Goulburn. At first, his parents didn’t question the random packages. “We would just sign for them and put them in his room,” says his mother. But it wasn’t just the boxes piling up that began to give them cause for concern. There was the Blue “Stessl” 560 Sea Hawk with an outboard motor parked in the empty lot across the street, which Milky had shipped there after buying it online.

Whenever his parents would ask where he was getting the money, he’d tell them, “Don’t worry, it’s nothing illegal.” Privately, they struggled to figure out what was happening. His father was quick to shrug it off, assuming Milky still had money from his home sale or, as he puts it, “must have won the lotto.” But his mom wasn’t so forgiving. “I figured he was selling drugs,” she says. She began searching his room for clues, checking his phone records and even his private email—which he had left open on his computer one day during a visit.

Milky’s parents weren’t the only ones given pause. There was many a morning when Milky himself would wake up in bed with, say, two strippers and a pile of coke, and have his own Talking Heads moments. How did I get here? What am I doing with my life? But then, as he tells it, “I’d go across the road, have lunch, have a couple beers, and then do it all again.” With his yellow smiley-face bandanna wrapped around his shaggy blond hair, his fat bankroll, and his generous ways, Milky became the Spicoli of Surfers Paradise, the go-to mate for a good time.

Shanyn Glover, who became his closest friend at the beach, recalls him regularly treating—or, in Aussie slang, “shouting”—drinks for everyone at the bar, buying her girlfriend a $600 tattoo, and bringing them when he returned to Phuket, where he handed them $2,000 to go have fun. One weekend, Glover and her girlfriend went with him to a car dealership in Brisbane, where he wrote a $92,000 check for a silver Aston Martin. He drove back, a smoke in one hand, a beer in the other, steering with his knees, no shirt, no shoes, no worries.

By 2012, two years after his first overdraft, he had his money system down pat: request a transfer from St. George to PayPal, then transfer that money to his National Australia Bank account for cash. He was taking out so much that he stopped keeping track or checking the balance of his debt. But he was easily in over $1 million (US$766,000). When he needed more than the $2,000 daily limit of cash withdrawals, he had an answer for that, too: taking out cash at his strip-joint hangout, whose owner would take 10 percent in return.

Milky’s rock-star lifestyle became routine. Sleep late, hit the gym, buy memorabilia online, slap the pokies, cocktails at the strip joint, then dancing all night in the clubs. On the nights he didn’t pick up, he sought the ready alternative: the many legal brothels in town. “Especially with girls,” he says bashfully, “you’ve got to make the most of every opportunity, because you might turn around and that’ll be gone.” One week, he threw down $40,000 and rented out an entire brothel to himself for four days. And so it was that, one day in November 2012, he barely registered what happened when he went to pay for repairs on his Alfa Romeo. He was standing there in the car shop, hungover and bronzed, when he saw a message he’d never seen before come up on the credit-card machine. “Call bank security,” it read.

Milky blinked a few times, trying to digest the moment he’d feared for the past two years. Fuck, he thought. Well, that’s done. He went back to his apartment in a daze. How could this just end? There was no old life. There was only this one, and the hole he had dug for himself. So he did the only thing he could think to do. He grabbed as many stacks of cash as he could find around his penthouse, drove to the airport, and booked the next flight to Phuket.

Her name was Pim, and she was beauuuutiful. Milky had met her during his first trip to Phuket. She was a young Thai woman who’d grown up poor on a rice farm. She barely spoke English, and he couldn’t speak Thai, but they had a genuine connection. One morning as he lay in bed with her, he thought how easy it would be to just stay in Phuket. He could sell his cars, cash in his memorabilia, move here, live with Pim in a beach house, buy a bar in town, run it with her, and—well, shit, who was he kidding? After two years of living like James Bond, he was still the bogan from Goulburn at heart. “It was that normal life that I wanted,” he says. “Not the, you know, leave my whole family to go marry a bird in Thailand and spend the rest of my life there.”

So instead, after a couple weeks in Phuket, he went back to Goulburn. He didn’t want to mess it up for the people he’d left behind. “If the debt collectors came around, I didn’t want the burden on my parents,” he says. Back at their house, he packed up what he could of his memorabilia, then reached for a Bible on the shelf—and drove his Aston Martin over to his friend’s. He told him he wanted him to watch the stuff for safekeeping. Then he cracked open the Bible, which was hollowed out with $50,000 cash stashed inside. Around 9:00 a.m. on December 12, 2012, Milky was in his bed at his parents’ house, on his laptop with his headphones on, when he heard a pounding on his bedroom window. He looked up to see two plainclothesmen outside. “Luke,” one said, “you got to open up. They’re at your front door banging, and if you don’t open it, they’re gonna kick it in.” By the time Milky headed for the front door, however, he saw his mother in her bathrobe already there with a look he remembers as “disbelief and confusion and sadness and anger all rolled into one.” As she recalls, “I was just in shock.”

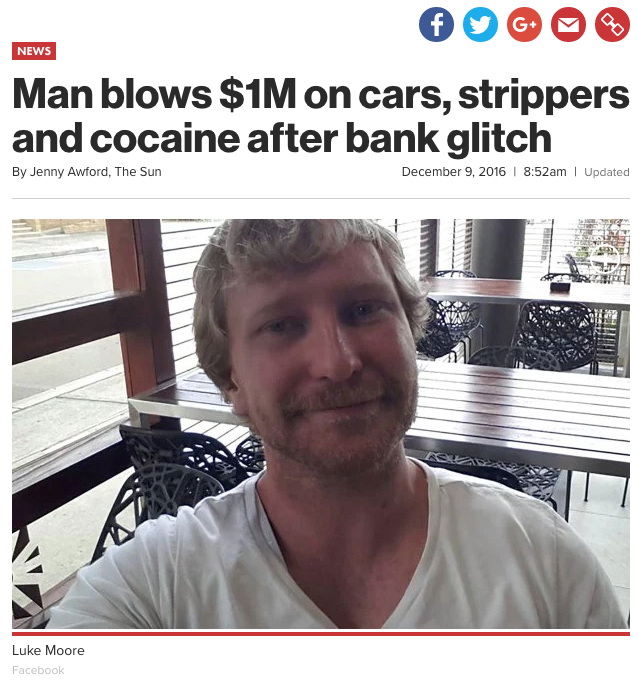

A group of police officers stormed in, waving a search warrant and brandishing video cameras. “Luke,” one said, “we’re here to raid your house.” They told him he was being charged with knowingly dealing with the proceeds of crime and dishonestly obtaining financial advantage by deception—for a total take, over the past two years, of $2,180,583 (US$1,671,201), including interest. Milky had no idea how he had gotten caught—perhaps someone at the bank had finally taken notice, or maybe someone on the receiving end of his large purchases had raised concerns. But he still believed that he had done nothing illegal.

There was one thing he couldn’t deny: the effect this was having on his mother. As the cops searched the house, all he could do was look at her, her wide eyes brimming with tears, the way she was grabbing her hair and saying, “No, no, no” over and over again, the way her face dropped when his father called from work and heard the news. And that’s when it really hit him, the reality of the fantasy he’d been living for the past two years. It had all led to this moment. “The regret, and the remorse, and the devastation on my part,” he says. “That I’d done that, that I disappointed them so much.” As the cold metal handcuffs snapped on his wrist, he leaned against his mother and whispered, “I’m sorry, Mum. It’ll be okay, it’s gonna be okay.”

On April 17, 2015, a Sydney District Court sentenced Milky to four years and six months in prison after he was found guilty of the charges. Not surprisingly, St. George was not forthcoming with details as to what had happened. A spokesperson for the bank would say only, to The Sunday Telegraph, that the glitch had been the result of a “human error” that had since been corrected. “The issue has been resolved and the customer has been convicted,” the spokesperson went on. “The bank is now seeking to recover funds.” The police confiscated Milky’s belongings and turned them over to the bank. Judge Stephen Norrish said the twenty-seven-year-old’s excuse that he was going to keep spending until the bank contacted him was “almost laughable...he thought he could get away with anything and he almost did.”

The scandal, which had been playing out in the national press since his arrest, had wrecked Milky’s family—and cost his father his job. “At a bank, integrity is a big thing,” as Brett puts it, and his mere association with his son was too much for his employer to bear. He ended up taking a demotion in rank and pay, leaving him out of sight in a back office. Annette, who had to be taken from the courthouse in an ambulance after breaking down over her son’s conviction, couldn’t forgive him, no matter how much she loved him. “I didn’t care about his dipstick rationalizations,” she says. “He was dishonest.” No matter how much he apologized, Milky could never forgive himself for what he’d done. “I fucked up their lives,” he says wearily. “I absolutely devastated them.”

Milky had plenty of time to ponder this in the Goulburn Correctional Centre. After his sentencing, he was cuffed, strip-searched, put in his green prison jumpsuit, and locked in a small cell with a toilet, a sink, and an angry Kiwi twice his size who was in on drug charges. When his parents came to see him in these conditions, his mother felt so overwhelmed that she collapsed in the visitors’ room before she could even meet him. She didn’t leave her bed afterward for a month. Milky hated himself for what he had done to land himself here. “You’re shaking your head at how much life could turn around in such a short period of time,” he recalls.

But he didn’t mope for long. From the moment the bars of his cell closed, he had a mission: to prove his innocence and get free. People could dispute the morality of what he’d done, he knew, but he hadn’t defrauded anyone. Problem was, no one agreed with him: not his family, not his friends, not the other inmates, not even his lawyers. If he was going to win bail and an appeal, he’d have to represent himself in front of the New South Wales Supreme Court. Well, he thought, I’m gonna have to figure it out myself. The challenge couldn’t have been more daunting: Could an unemployed bogan with a high school education take on one of the country’s biggest banks and convince a high judge to overturn his conviction?

But Milky was determined. He hit the books sent to him by legal aid. He read Criminal Law and Procedure, a fat tome that taught him the basics of the profession, and then focused on cases of fraud and deception. After a few months of research, he found a tiny ray of light. According to the law, he discovered, deception meant that he had to have caused an unauthorized response from a computer— a charge, he knew, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

According to Milky’s contract with the bank, he was perfectly authorized to receive overdrafts subject to the bank’s approval. In practice, when Milky put in an overdraft request, it would get sent up from his local bank to a corporate “relationship officer” for sign-off. But if the officer didn’t respond within a certain time frame, the request would automatically get approved—which is what kept happening for him. In other words, as the bank admitted in court, it was its own “human error,” and had nothing to do with his getting unauthorized access to a computer at all. It was scapegoating him for its own mistake and his lawyers had botched the case, he fumed. “It was a long shot for the prosecution to even come after me the way they did,” he says. “And I don’t think anyone in the jury understood it.”

As he prepared his case, he stayed up all night writing out his position in pencil and taping the pages on the wall of his cell. By the end, he’d written 120 pages—citing case upon case, laying out his argument. Knowing he couldn’t just read twenty thousand words to the judge, he memorized them as best he could instead, pacing back and forth as he recited them over and over again. And he did it all without the support of those dearest to him. “We thought he was crazy,” his dad says. “There was no way he was going to win.”

Finally, on August 6, 2015, four months after he began his research, Milky got his shot. Dressed in his prison khakis, he stood nervously before the video link that connected him to the New South Wales Supreme Court. Justice Peter Hamill didn’t seem to take Milky’s chances seriously, urging him to be expeditious. “There’s other court cases apart from yours,” he told him over the video feed.

But from the get-go, Milky sounded very much like a real lawyer. “I’m going to show as a matter of law what may involve complex legal reasoning, the application of relevant case law, and the thorough and careful analysis of the fraud-defense provisions, the conduct I engaged in—the requesting of and the carrying out of the transfers of funds—does not come within the scope of any statutory or common-law definition of ‘deception,’ and therefore the fraud defense cannot be proven to the criminal standard as required by law.” Citing relevant cases, he admitted that while many might find what he had done immoral, it was not criminal by any definition. “It wasn’t a computer that responded to my request,” Milky said, “but it was staff who actually responded and resulted in an approval of the transfers.”

Finally, after four hours of hearing from Milky and the prosecutor, Justice Hamill came back after a break with his decision. “Mr. Moore,” he said, “I’m granting you bail.” Milky thrust his hands in the air victoriously, then quickly composed himself and thanked the judge. Next he called home to share the incredible news. “I’m getting out!” he told his parents. “You’ve got to come pick us up!”

On December 1, 2016, the New South Wales Court of Appeal ruled in his favor too. “The unusual aspect of Mr. Moore’s conduct was that there was nothing covert about it,” Justice Mark Leeming noted in his judgment, adding that St. George bank had chronicled “with complete accuracy Mr. Moore’s growing indebtedness.” St. George declined to comment on the acquittal, though it later contacted Milky to tell him it was not coming after him for his remaining debt. It was obviously in the bank’s best interest to let this fade as quickly as possible. As Milky left the courthouse a free man, a reporter from the tabloid TV show A Current Affair trailed him, cheekily asking if he was going to drive home in a Maserati. “Not today,” Milky told her with a laugh. “Not today.”

On a hot summer weekend at Surfers Paradise, Milky and I return to the scene of—well, not the crime, the fantasy. He hasn’t been back since he left years ago, and brightens nostalgically as we wander around his old digs. The blue skies. The endless powdery white crescent beaches. The surfers riding the wide, crashing waves. The young, tatted, tanned women, as ready to party as he is. “Beauuutiful,” he says with a rosy grin and a sigh, taking a puff of his hand-rolled cigarette.

In the wake of his acquittal, Milky’s story went viral online. Astonishingly, this wasn’t an isolated mistake by St. George. On May 4, 2016, a twenty-one-year-old college student in Sydney was arrested for spending $4.6 million on designer handbags and jewelry after getting her own unlimited overdrafts from Westpac, a subsidiary of St. George. This raises the question: How many other such cases are out there, and what would others do if they had the chance? Or, as Snoop Dogg posted on Facebook, along with a link to a newspaper story on Milky, “What would yall do?” When asked what he’d do if given the chance to do it over again, Milky is ambivalent. “I’m not 100 percent sure whether I wouldn’t have done it at all,” he tells me over a beer. “Or maybe I would have stopped sooner, or maybe I would have played my cards better and buried some more of the money.” His eyes widen at the idea. “I could have ended up with $50 million,” he goes on, “bought a private island in a nonextradition country, had brought suitcases full of money, maids and bloody chefs and that working for me the rest of my life. Moved my whole entire family.”

Instead, he plans to make his fortune the old-fashioned way: by working, as a criminal lawyer. After successfully representing himself in his case, he found his calling. He’s currently enrolled in law school and expects to get his degree this spring. And what will he do if he ends up making millions again? “I reckon I’ll have to move back here,” he says with a smile, which would be the most beauuuutiful ending of all.